For the second time in recent years, Fred Khumalo has taken a historical event and woven a fictional tale around it. The Longest March is primarily a love triangle

between Philippa a coloured lady, Nduku a suave black man and Xhawulengweni a tsotsi from a forgotten era who is also Nduku’s ex-lover. However, the story is much more than a love story. It is an exploration of race, sexuality, interracial relationships, the resilience of the human spirit, the influence of early Christian missionaries on race relations and lots of Zulu mythology.

The historic event that forms a background for the story of Nduku, Philippa and Xhawu is the evacuation of Zulu mine workers from Johanessburg as the second Boer war approached. First to leave the city were the white people and by the end of September 1899, the black (mostly Zulu mineworkers) were still stuck in the city as disaster loomed. With no transportation available (trains had stopped running as the war loomed closer), they started a long walk from Johanessburg to Zululand (Newcastle and Natal). The walk lasted over eight days. The entire plot of the book takes place within the time frame of this great march.

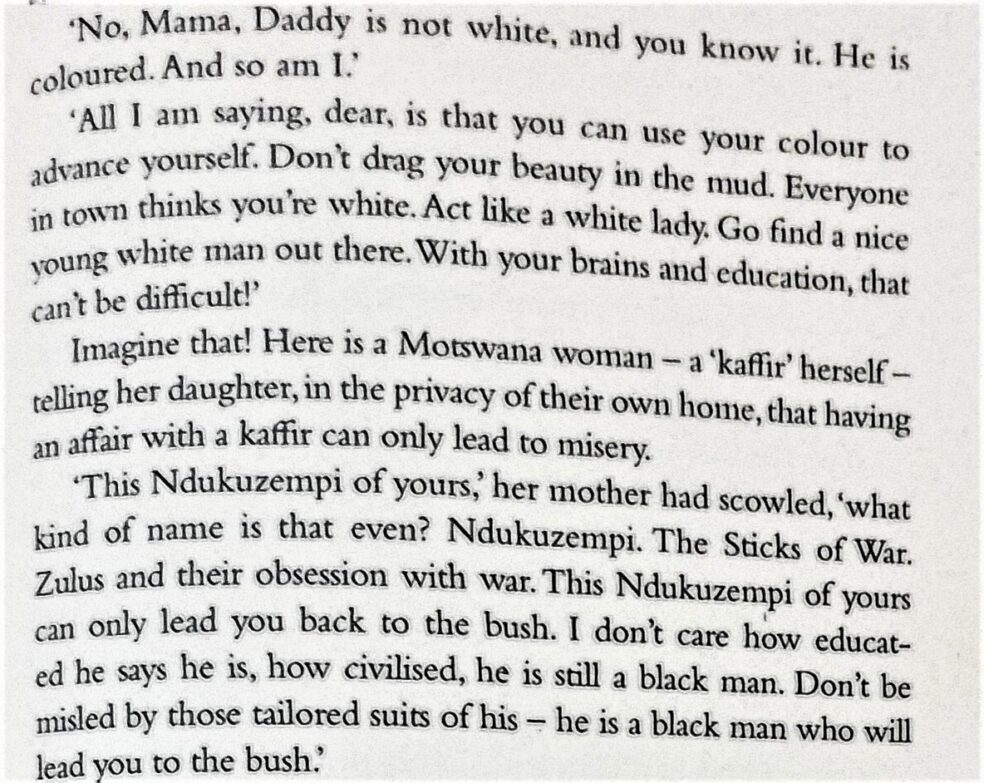

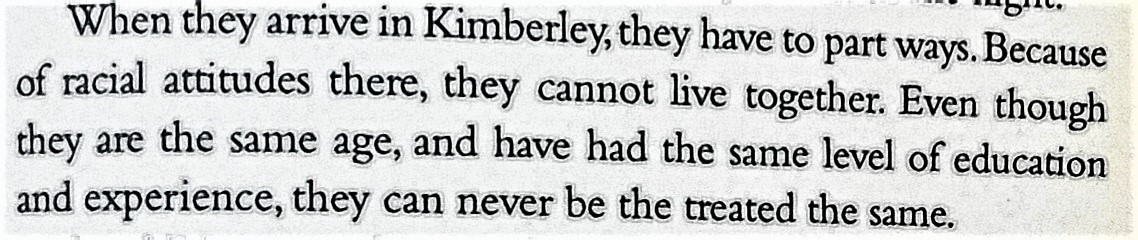

Colourism is a theme that is very obvious in The Longest March. Philippa’s skin tone marks her out for certain privileges that her own black mother can only dream of. She is looked up to like a benefactor by blacks because she is dating Nduku. It is assumed that she is dating down. While she is lauded and treated as such by blacks, the whites are disdained and let down by her choice of a lover. It is ridiculous but real. Beyond her skin tone, she is a steadying influence on Nduku – a man who is running from his past and is scared of committing to anything or anyone. What he lacks in assertiveness, Nduku tends to make up in loyalty. He is loyal to Muhle to a fault. Whether it is loyalty or an inferiority complex is up for debate.

In Xhawu we see contradictions of all sorts. A thug who uses bible quotations to marinate his criminal enterprise. The contradictions do not end there; he is also a heavily built thug who is tender-hearted. This is evident in the letter he wrote to Philippa and Nduku at the end. Beyond Xhawu’s contradictions, it is also interesting to note how the ministry of the early Christian missionaries as depicted in The Longest March perpetuated racial discrimination and an inferiority complex in its early converts as seen in the lives of Xhawu’s parents and Nyembezi. The faith had not empowered their personalities and this is another contradiction. In all of

In all of these, Fred Khumalo brings to live an epic historical event with his well-developed characters and descriptive dialogues. For an outsider like myself, there might have been too much Zulu culture and mythology embedded in the story but it is an enjoyable read all the same. The resilience of the characters in the face of the torturous journey makes for an interesting read. There have been a few exceptional African historical fiction novels in the recent past; Kintu, Half of a Yellow Sun and the lesser-known, The Catastrophist. The Longest March may not punch high enough like those but it makes a good showing and is worth the read.

3.1/5

1 Comment

Pingback: Touch My Blood (Bonus)