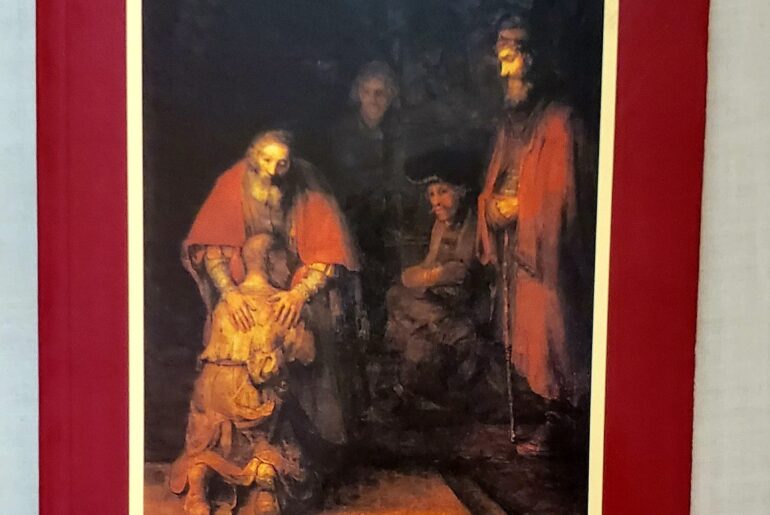

The cross and the lynching tree. Two symbols of humiliation, torture and killing. The former, common in the first century Roman Empire and the latter, common almost two thousand years later in America. At first, the similarity is not obvious but when you engage this historical exploration by James Cone, you see how the cross at Calvary has served as an aid and hope for the black American society as they came to terms with the symbol of the lynching tree both figuratively and literally. And because one can lynch a person without a tree or a rope, the lynching tree remains an indicting rod for the white American church back then when juxtaposed with the centrality of the cross in the Christian faith.

The Cross and The Lynching Tree is a small volume (166 pages without the copious references) that packs a tremendous punch. In it, James Cone outlines not just the history of the lynching tree but how the centrality of the cross and Jesus’ crucifixion served as an anchor and source of hope as black Americans faced the evil of white supremacy depicted in the lynching that went down in America’s south. Just as the crucifixion of criminals on a cross in the Roman Empire was an instrument reserved for insurrectionists and rebels, white supremacists used lynching to instil fear and shame in those who dared to rebel against her dignity of slavery and racism. The fact that the cross was (and still is) God’s critique of power with powerless love, snatching victory out of defeat emboldened the black American church to face up to slavery and its offshoots like the lynching tree. Ironically, the white church was largely ignorant of the reflection of the cross as it showed up in the lynching tree. James Cone was particularly critical of Reinhold Niebuhr who despite his theological prowess was unable to expound that while the cross symbolized God’s supreme love for human life, the lynching tree was the most terrifying symbol of hate in America. The lukewarmness of church figures like Reinhold Niebuhr is a criticism that James Cone repeatedly returns to and it is a very poignant one. A criticism that when evaluated fully, exposes the hypocrisy of the white American church and criticism that reminds one of the Afrikaans church in South Africa during the height of apartheid. They found reasons to justify racial segregation and the subjugation of blacks in their own land. Most interestingly, James Con’s criticism of Reinhold Niebuhr reminds me of the difficulty I still have with Paul’s letter to Philemon in the New Testament. I have struggled to reconcile the content of that letter with Paul’s message of the new birth and the kingdom of God. Why was he not bolder in denouncing slavery in that letter. Why did he not tell Philemon that Onesimus was not an object to be owned and that in God’s kingdom there was no master nor slave?

The Cross and The Lynching Tree is an impactful book that looks back in history and reveals the hypocrisy of a part of the American church, the struggles and hope of another part of the church and both revelations are through the prism of the cross. It is thoughtful, provocative and instructive, all at once.

3.9/5