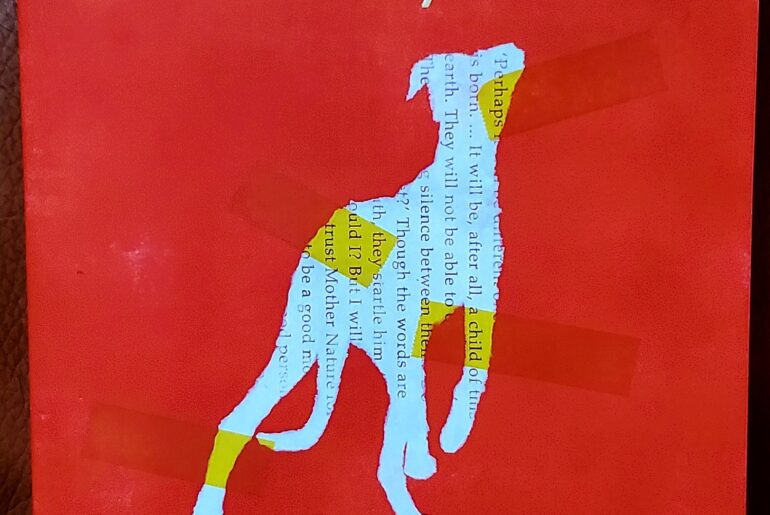

I had mentioned in an earlier note that I have three works of fiction set in India in my 2021 TBR list. The Year of The Runaways is the second of the three. Sweeping between India and England (mostly Sheffield) and between the early teenage years of its protagonists and present-day, The Years of The Runaways follows the lives of three young men who have been pushed by poverty and other excruciating family factors into a desperate search for a new and better life. Tarlochan (Tochi) is a former rickshaw driver who refuses to say anything about his traumatic family life in Bihar before he migrated illegally to the UK. Avtar has taken great risk to the point of organ harvesting to make the journey to a land where he thinks his fortune will be turned around. Randeep whose chaotic nature means that Avtar has to keep protecting him. Avtar has a student visa for which he is not interested in schooling. Randeep has a visa wife (Narinder). Their reasons for migrating differ but the desperation of their actions and the grimness of their lot while in England is uniform and almost indistinguishable.

From afar each bears the burdens of their families and each is the candle that keeps the hopes of their families from being extinguished. It is a heavy load to bear and made even heavier by the illegality of their stay in the UK and the unavailability of decent enough jobs to service the enormous loans that facilitated their migration. All of these make The Year of The Runaways a very painful and grim read but one that is grounded in the reality of what life is for the average migrant who is seemingly helpless enough to dream of migration as the only option in the face of shrinking options at home.

In the midst of the gloom and suffering that encompasses the three male protagonists is the welcome diversion of Narinder, Randeep’s via wife. Narinder’s character is a welcome diversion not just because she is not a migrant (she is British of Indian origin) but also because her characterisation lacks the three male protagonists. Apart from their background, nothing separates Avtar and Randeep and their lives in England is basically interchangeable. There is no depth in their characterizations. Her battles and internal conflict between spiritual devotion and human empathy, between the chains of patriarchy and freedom and that between innocence and loss, are keenly observed and her character evolution is apparent.

Altering between four protagonists was always going to be tricky but what makes it worse in the case of The Year of The Runaways is the lack of depth and similarity in the characterization of the male characters. This made it difficult to track which character was in focus most of the time. The Year of The Runaways is sustained by the realism of the plot. However, it is let done by the workmanlike nature of the prose. It reminds me of a recent discussion I read online where someone said some fiction writers are storytellers while some have a gift for writing and that very few have both. After reading this book, I am inclined to believe that Sunjeev Sahota is more of a storyteller. This is not one of those books where you are captured by a sentence, quote or paragraph. It is one where you recognize the reality of the plot and empathize with the characters without finding any of them memorable.

3/5