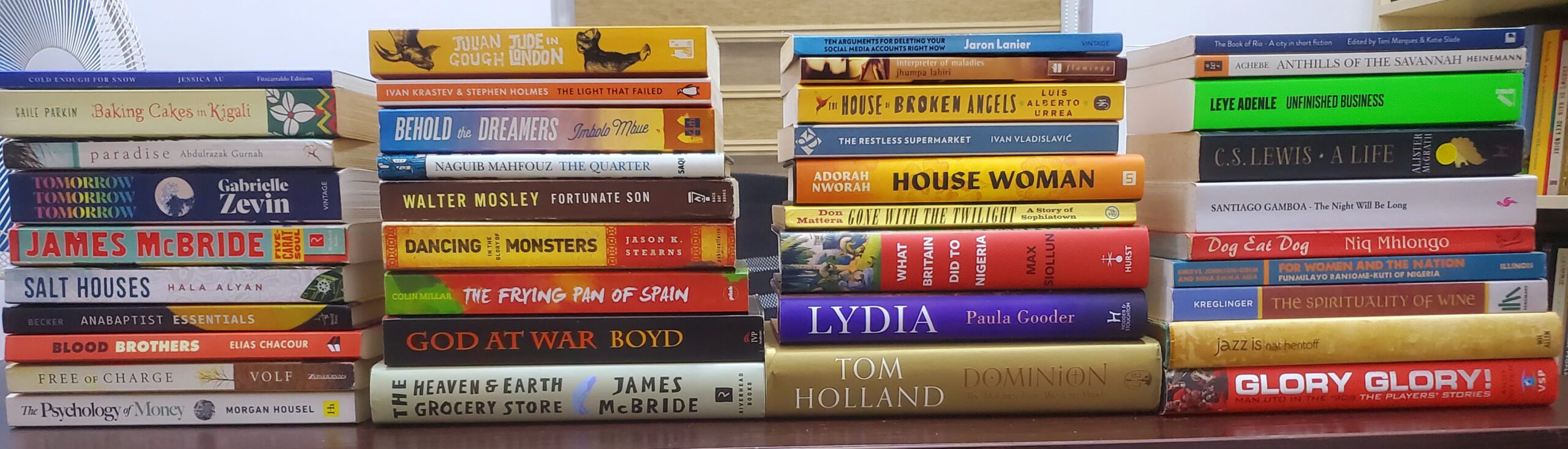

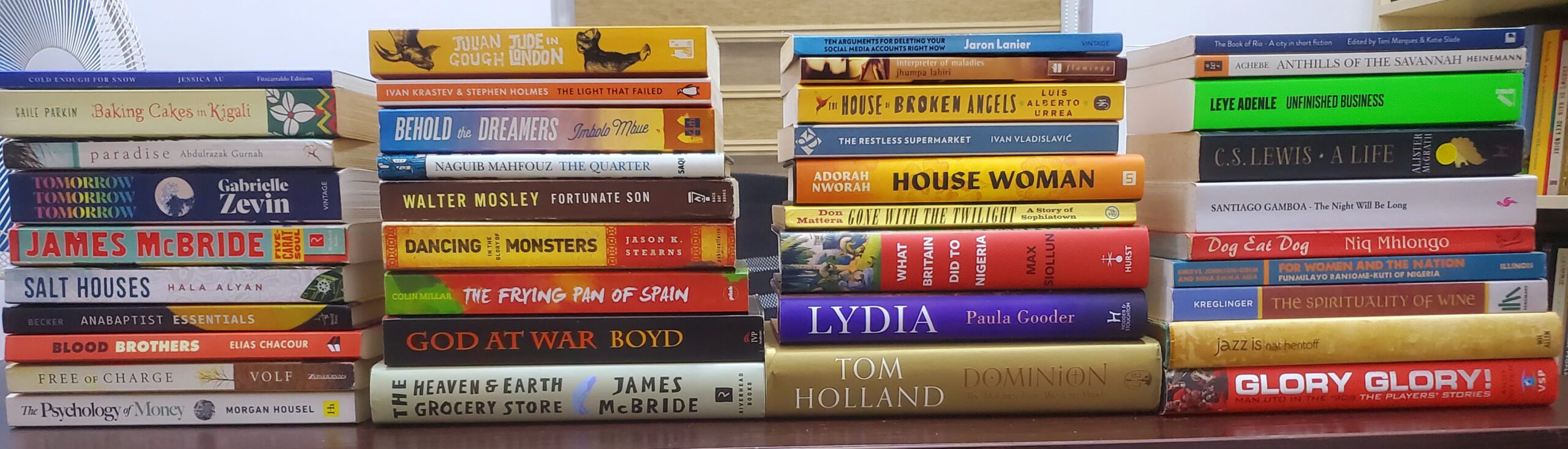

Nothing signals a new year for me like my yearly TBR list. That time has arrived and after the process detailed here, this is it!

I look forward to the journey and whatever you are reading this year, happy reading!

Nothing signals a new year for me like my yearly TBR list. That time has arrived and after the process detailed here, this is it!

I look forward to the journey and whatever you are reading this year, happy reading!

One good thing about finding solace in books is that no matter how bad the year is, you are destined to have highs in the pages of the printed words. 2023 was not the best of years for me but I can look back with fondness on most, if not all the books I read. Looking back, I may not have enjoyed the 2023 TBR list as much as I anticipated when I settled on the list; mostly due to external factors and not necessarily based on the quality of the reads. However, it was a good year with books. Doing this a bit differently this year, I have chosen the following 5 books that I enjoyed the most. 3 of them are fiction and the remainder are non-fiction.

Despite having read only one book by James McBride before this year, I consider him one of my favourite novelists. I was completely blown away by Deacon King Kong when I read it a few years ago. Now reading his memoir based on the life of his mother, his position in my rank of writers is further cemented. It is storytelling at its best, as James McBride makes both the sublime and mundane resound in exquisite prose. The Color of Water is easily one of the best memoirs I have read in the last few years.

Rohinton Mistry’s Fine Balance is one of the most impactful works of fiction that I have ever read. It is one of those books you read and conclude that the author will never come so close again. Not because you doubt his ability and craft, but because the work is so close to perfection that it can’t be equalled or bettered. This was the context in which I approached Family Matters this year. It did not match up to Fine Balance but almost no other book would. However, Family Matters is proof that Rohinton Mistry is the master of the subgenre of family saga fiction. Very few writers can write a compelling tale out of mundane family sagas and everyday life. Family Matters is an excellent specimen of that.

While I have had a couple of Petina Gappah’s books on the shelves, Rotten Row is the first of her works that I got to read. Like most collections, there are hits and misses, but the hits far outnumber the misses. I particularly enjoyed Copacabana, Copacabana, Copacabana and In The Matter Between Goto and Goto. The former is set in the city centre and mostly in a public transport bus. That is a setting that contains a recipe for excellent short stories. The latter is odd, creative and very thoughtful.

I have a thing for migration tales. They reveal a lot about the human condition. I have read a few good ones in the last few years and this year I read The Son of Good Fortune. I consider it the best of all novels I read in 2023. While the writing is not the best, the story, the pacing and the subtle hints in the storyline leave for a very impacting experience. It explores the human condition exceptionally well and at the end, one is forced to ponder for a bit. The themes of belonging, definition of home and survival are all explored in this relatively short volume.

A Good Provider Is One who Leaves

Ever since I read this book, I think about its content often. I refer to it in conversations and it has provided an extra lens to view 21st-century migration. It is creative non-fiction at its best; exploring the path of several generations of a Filipino family as they seek opportunities abroad to better the lot of their family. A most excellent read it was.

As usual, in all the books I have read this year some quotes, phrases and paragraphs have resonated with me this year. These paragraphs are not limited to these top 5 books. Below are 5 of the best paragraphs from the books I read.

Last year’s Booker Prize longlist nominee, Nigthcrawling, is a meditation on the powerless and a study of compulsive maternal instinct where the protagonist attempts to save every swimming person around her while drowning herself. 17-year-old Kiara grows up in the projects of Oakland, Her family life is as broken as can be. Her father, an ex-Panther and ex-convict, has passed away, her mother is in a halfway house on her way to parole after a stint in jail and her beloved brother Marcus is refusing to live in the real world while convinced that his way out of poverty is the lottery of a rap music career. Thrust into the role of a provider, not just for herself but also for her elder brother Marcus and the abandoned kid, Trevor, in her building, Kiara opts to sell the only thing that seems available to her; her body.

Nigthcrawling is an exploration of misogyny, poverty, exploitation and abuse. The exploitation in it often felt too raw and the poverty in your face and almost traumatic but when you align to the fact that as fictional as it is, this is the reality of some people, it is humbling. Nigthcrawling is based on a real-life story where a group of police officers were investigated for exploiting underage girls. While the plot is striking and concerning, the writing strikes the opposite tone. It is problematic since the protagonist is a 17 year old and the tone is expected to be generic and street-savvy. The problem is that for the kind of topics it treats, Kiara’s voice in Nigthcrawling is generic and devoid of passion. In general, the writing is clunky and too descriptive. It made poignant highlights not stand out and made it hard for the reader to feel the emotion of the relatively difficult topic. There is so much to like about Nigthcrawling but for a Booker Prize longlist, one expected a whole lot more.

3/5

I found The Black Church by Henry Louis Gate Jr. soon after reading The Cross and The Lynching Tree a few years ago. It is an interesting read, particularly considering my Anabaptist inclination. I say that because The Black Church is a historical survey of the African-American church, which means that it covers a wide range of the African-American religious experience, mainly the Christian faith and how the church intersects with the political, as well as the cultural and social spheres of the emancipation and beyond. It explores the evolution of the Christian faith within the black community in America starting from the times of slavery till the Obama presidency until the Coronavirus pandemic. It surveys the impact of the Christian faith on the social, political and cultural lives of the black people over the past 2 centuries. Socially, the impact of slavery impacted how the black community evaluated the Christian faith and embraced it. Politically, the segregation that the black community experienced ensured that the equality of all men that black Americans saw in the bible was a hopeful aspiration that contradicted their lived experience but gave them a reference with which to fight for change. Culturally, they reshaped the gospel they were given by infusing their aspects of the black culture from their African ancestry. The Black Church highlights how the black culture has fed the music and dance worship experiences of the black church. As a person for whom the Negro Spirituals have had a profound meaning, the ability to infuse hope into a bleak situation is captured in tracks like Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child. After Emancipation, the Black church retained its importance in nurturing Black culture and helped to foster political action. The pulpit became an extension of the campaign arena as Black Americans sought not just the end of slavery but sought the vote, an end to segregation and even an end to police brutality in the present day. The Black Church highlights the pivotal role that the church has played for black Americans.

The Black Church like The Cross and The Lynching Tree highlights the social impact of the Christian faith in the context of black American society, it also raises many questions about the complicity of the church outside the black church then and now. In bringing it home, while I am unequivocal about my belief that the church and the state should be separated, it is obvious the role the black church has played in the emancipation of the black man in the American polity, it then begs the question the dubious role that a large portion of the Nigerian church keeps playing in perpetuating evil within the Nigerian polity and propping up wicked political leaders.

The Black Church is excellently structured and paced. It may be lacking in depth and overly reliant on the works of W. E. B. Du Bois, and being a companion of a TV documentary, it is quote-heavy, it is a good introduction to a very important and illuminating topic. Very good read.

3.6/5

If I were to attribute any good in my Christian faith to anyone the list would start and likely end with the following; C.S. Lewis, Selwyn Hughes and Gregory Boyd. While all the bad is completely down to me, those 3 have been pivotal to me having any faith at all. I first encountered Seleyn Hughes in the late eighties while in secondary school. Devotionals were as popular back then as early morning online prayer sessions are today in Nigeria. Every Day With Jesus was a regular feature in almost every Anglican and Baptist family. It helped readers study the bible in a themed manner. In-depth studies of topics were covered on a daily basis and 6 editions were covered in 12 months with each edition running bi-monthly. It helped to inculcate a daily bible reading practice in most families. It also cultivated a practice of meditation as each daily reading contained specific bible verses that could be reflected upon the whole day. Every Day With Jesus was and still is thoughtful and reflective in a way that was relevant for new believers and mature believers alike. Reading Every Day With Jesus daily was an act that developed spiritual discipline, writing it was a greater act of discipline for Selwyn Huges. A discipline he developed and practised for over 40 years. It was through his writing that I first encountered the works of C.S. Lewis. Selwyn Hughes always referenced C.S. Lewis when discussing the problem of pain and how the Christian faith grappled with the issue of evil in a world created by a good God.

My Story is the biography of Selwyn Hughes. It is the story of a boy born in a mining town in the south of Wales who grew to impact the world for his God. Told in a straightforward manner and with a sense of humbling honesty, My Story reads like an Actod of the Apostles. Sewlyn was a man full of activities and projects. The major point that came out of his projects and activities was that they were impactful for the kingdom. He found a niche and did not deviate from it. Devotionals and training Christian counsellors were his forte and he made a mark in them. My Story traces the journey from Selwyn’s childhood to his early days as a pastor to the launch of Crusade for World Revival (CWR) which was the vehicle for his writing and counselling ministry. The majority of My Story is about Selwyn’s ministry and is full of names, places and facts. However, there is very little about his life outside the ministry. While there is a bit mentioned about his wife, Enid, and a few mentions about his two sons, there is not much detail about his family life. For a man who struggled with the sudden death of his two sons, his wife suffered and died of cancer and he succumbed to the same disease, yet, there is very little of how he dealt with those painful moments. In all, My Story is a worthwhile read (if not particularly exciting) of an extraordinary life.

3.1/5

C.A. David’s How To Be A Revolutionary explores the complicated question of what happens after a revolution. It is a multi-layered exploration of political struggle, commitment to a cause even in the face of betrayal, and the contradiction of power. At its core are four narratives; Beth’s past and present, Zhao’s past and present, Langston Hughes’s letters to an unnamed correspondent in Cape Town, and Beth and Zhao’s friendship in Shangai. Both Beth and Zhao have been loyal to causes that they believed were revolutionary in their own parts of the world. Beth and her high school friend, Kay, got involved in the anti-apartheid struggle while teenagers and despite life-threatening circumstances, Beth remained a comrade. Zhao was a journalist who experienced the Chinese Great Leap Forward and the June 4th in Tiananmen Square. Both have secrets that make them question the sacrifices of the past in the light of the present. For Beth, the ruling party has gone from being liberators to being the oppressors themselves (I am reminded of the famous Smut Ngonyama’s comment; “I did not join the struggle to be poor”). She constantly finds herself trying to be pragmatic in the face of the contradictions of power that are manifested when the liberators are in power vis-a-vis when they are fighting oppression. There is not one way to handle this contradiction; Andrew, Beth’s ex-husband shows an alternative. Each has to live with their choices. For Zhao, it is the horrific and catastrophic outcome of the Great Famine where many lost their family to starvation while others manipulated the rations and fed fat in the process.

The narratives go back and forth between both characters. The narratives are fused with the present interactions between Zhao and Beth, who live as neighbours in a Shangai block of apartments – Beth is a diplomatic staff at the South African embassy and Zhao is a retired journalist. They strike up an awkward friendship. One that ironically engenders a deep trust that changes Beth’s life. How To Be A Revolutionary is a book that expertly zooms in and out, one moment local, the next moment global. The disenchantment that Beth feels about post-apartheid South Africa is akin to that felt by Zhao about his mother’s death and the Tiananmen Square events. In all, I found the characters well-developed and the moral complications that they had to grapple with to be revealing. The only downside was the Langston Hughes narrative. I found it largely distracting, relatively flat and an unnecessary angle that added little to the overarching storyline. in all, How To Be A Revolutionary is an exploration of shrewd observations that are encapsulated in beautiful minimal prose. A fine read.

3.5/5

It was when I picked up this book to read that I remembered how I ended up buying it. I stumbled on a Twitter (I am not up for that X thing here) handle that was an authority of sorts in English-translated Arab Literature. I slid into the DM and asked for recommendations of novels that matched my taste. In The Country of Men was not one of the 3 books recommended but it kept popping up in the reviews of those books, so I decided to check it out, I ended up buying it and 3 years later it rose to the pile of my 2023 TBR list. An added point was that it was not a translation but originally written in English.

In The Country of Men is a novel set in Libya in 1979. The main protagonist is a 9-year-old Suleiman. In 1979, Muammar Gaddafi’s authoritarian rule was in full swing. Freedom was an alien concept in the polity and, full and coerced obedience was the order of the day. The slightest defiance was met with arrest, torture and even death by public execution in some cases. It is in this world of palpable fear that Suleiman is growing up in a middle-class family. In The Country of Men is told through the eyes of a boy and this child protagonist’s storytelling serves myriad purposes as it aids the writer to be vague in different ways; the plot is loose and almost open-ended, and a lot of decisions are left unexplored and the reader is left to make up his/her mind. It could be frustrating for many readers but it also seems plausible because this is a 9-year-old protagonist in an environment where distrust, fear and suspicion rule. It makes sense because he is unsure of most of what is happening around him. His father goes away on repeatedly undefined business trips and when he is home, he is holed in his study reading any one of his very many books that seem out of bounds to everyone else. Every time his father is away, his mother is always ill and always in need of a special liquid medication that is only available from the local grocery shopkeeper. To the reader, it is obvious that Najwa, Suleiman’s mother is an alcoholic who only gets a chance to indulge in her addiction once her husband is away and it is a secret her son has to keep despite not being fully aware of her illness. Faraj, Suleiman’s father is a democratic activist who is involved in the underground civil disobedience movements and his regular business trips are actually trips to the discreet apartment in the city centre where he and his comrades meet to plan their disident actions.

Suleiman begins to see how unsafe the country is when Ustath Rashid, the father of his best friend Kareem, is abducted by the Revolutionary Committee for being a traitor to the Gaddafi regime. Suddenly Faraj’s library of books has to be discreetly burned before the Revolutionary committee cone looking for Baba too. The secrets that are kept from Suleiman or that he has to keep are too weighty for a child of his age but this is Gaddafi’s Libya; secrets, distrust and fear are the currencies of daily living. Nothing like the Libya that Social Media Pan-Africanists fantasise about. Baba gets arrested, tortured and returned back home, broken physically and emotionally. Tough decisions are made and from afar, as a 24-year-old man, Suleiman reminisces on his childhood and the losses that have shaped him.

Hishom Matar’s prose is eloquent as can be, coming from the voice of a 9-year-old. His description of Najwa’s loneliness was particularly poignant as was Rashid’s torture and execution. In The Country of Men is a good read although the plot is loose and the pace is too slow.

3.2/5

Japa, which is the Nigerian slang for migration is a Yoruba word which means “to flee”. Migration has always been a thing among the Nigerian elite and upper middle class. From as far back as a century ago, young and even not-so-young Nigerians have travelled abroad to further their education and often either stayed back to work or returned to resume their careers. However, this current trend has made Japa a buzzword in the Nigerian social media lexicon and a recurring topic on its radio stations is unique. The steep economic decline in the polity followed by a persistent wind of globalization for opportunities and talents has made migration a hot-button topic that has refused to cool over the last decade. Literally every urban dweller in Nigeria, irrespective of social class has several anecdotes centred around the Japa syndrome.

A few of these anecdotes have led me to reminisce on the works of fiction that I have read in recent months and years. The verisimilitude of migration fiction is a global feeling. The world has become a global village and migration is not just a Nigerian thing. Whether in Filipino fiction, Nigerian fiction, Indian fiction, Mexican fiction or Ugandan fiction, people are leaving home as they know it and making a new home far away. People are even beginning to reconsider the meaning of home as a concept. Many Lagos residents of eastern Nigerian origin who were born in Lagos and considered Lagos to be home were forced to reconsider what home meant during the last elections. They were suddenly made to feel less than equal and alien within their own country. A good portion of such Lagosians are leaving in search of new homes abroad due to the oppression that has made them reassess their definition of home.

For all the charms of native lands; hunger, oppression and destitution are continually fuelling Japa. Young and not-so-young persons are leaving Nigeria through various routes; you have those who are using the education route – selling assets and possessions and barely surviving abroad in a bid to get a foreign degree that would provide a chance to advance in a new land. This is the route explored in The Year of the Runaways. In it, one of the protagonists goes as far as selling one of his kidneys to be able to fund his migration to the United Kingdom. As economic conditions worsen for the middle class, such fictional tales will be sadly mirrored by reality. The Year of the Runaways is full of people who left destitute homes to meet a set of circumstances different but not distinctly better in a new land. Another sorry state of migration is found in the short stories collection – Better Never Than Late. People like Gwachiwho live duplicitous lives all in a bid to sustain a new life in a new country.

Japa is not restricted to those migrating through the education route or dubious marital relationships as seen in The Year of the Runaway, Better Never Than Late and Dominicana, there are also those who migrate as professionals, as seen in some of the stories in the Short Stories collection, Manchester Happened. This is also the route explored in Travellers. For this set of migrants, despite their professional achievements, a sense of unease remains because rightly or wrongly, they overanalyse every interaction and sense that despite the welcoming smiles, the natives do not see them as equals and even simple questions like “Where are you from originally”is loaded and unsettles them a lot as they rightly expect that their professional attainment and social standing in their new home should make them equals to anyone else. Another set of migrants are first-generation natices. Children of migrants who are born in a new country are continually defined by their parents’ illegal status. This is excellently captured in The Son of Good Fortune. The concept of home is hazy to this set of migrants’ children. They do not feel fully accepted in the country where they are born yet it is the only place they know to call home.

In all of these books, there is one common thread; humans will always gravitate to new lands in a bid to beat hunger, oppression and alienation. The routes for that gravitation differ and the experiences are varied and multifaceted. As Japa intensifies in the face of the relative hunger and oppression in Nigeria, the narratives explored in each and every one of these books will be the lived realities of more Nigerians.

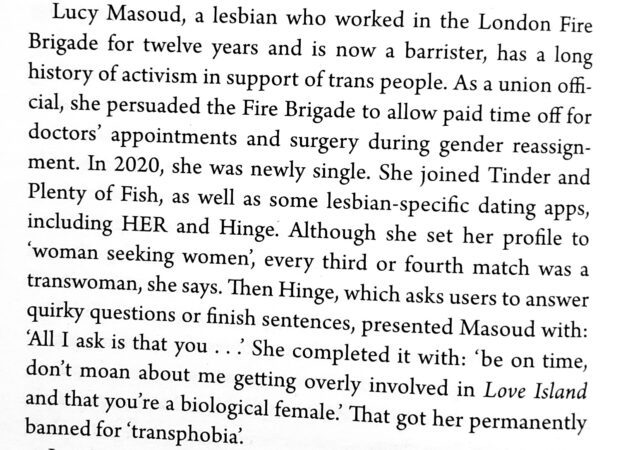

Soon after reading Helen Joyce’s TRANS, I decided to amuse myself a bit by looking through reviews in publications and websites across the Culture spectrum. I found it amusing because it was an exercise in how bias shapes narratives. Those on the left denounced TRANS and its author, calling it poorly researched and full of holes. Those on the other side called it groundbreaking and a true assessment of trans activity. What is unamusing is the seriousness and urgency of the issue that TRANS tackles. At its core, the issue that TRANS explores is how gender self-identification redefined gender as something innate and personal. A feeling that cannot be questioned but only believed and not dependent on biological sex. Even when it is innate and based on feelings, it must not only be accepted by all but redefine how a major section of society lives their lives.

This is not a book that disputes the lived experiences of transgender persons. What TRANS does is question the push by transactivists to not only lower the bar for transgenderism to self-identification but also delegitimize the supremacy of biological sex to the point that anyone who points out the disconnection is labelled a heretic and a human rights abuser (I am ignoring all those fanciful terms used in such occasions). The pivotal premise of TRANS is that the current trend anchored on the push described above is harmful to biological women. TRANS explores how transwomen have, while insisting that innate feeling is sufficient to identify with a new gender, also forced biological women to see transwomen as women in all circumstances. How this impacts women’s spaces, prison facilities and sports are areas where the gender self-identification ideology clashes with the reality of everyday living.

Reading TRANS, I get the impression that the author’s passionate exploration of the topic is solely because women are gravely impacted by the gender self-identification ideology. The fact is that the impact is more far-reaching. The “I feel, therefore I am” form of liberation was always going to lead to this logjam with devastating consequences for reality. Feelings can never be enough to determine societal norms. It can be used for religious creeds but those are never imposed on non-adherents. Redefining what constitutes womanhood based on such broad criteria was always going to be problematic. Pronouns are being muddled up arbitrarily, dissenting voices are being silenced with vehemence and women’s sports are suddenly an all-comers affair. TRANS highlights the danger to women and children but it looks like the danger will be all-encompassing as long as “I feel, therefore I am” remains a leading mantra of post-modern liberation.

3.7/5

Before and shortly after apartheid ended, there had been a large catalogue of South African fiction that dealt with the societal issues of the South African polity centred on the racial divide and its attendant inequalities. In more recent years, there has been a dearth of such stories, largely for good because a permanent view in the rear mirror is no productive observation of any society. In light of the recent trend, They Got To You Too is a refreshing take in the sense that it revisits the past when it gets Hans Van Rooyen to look back at his life of privilege, regret and search for renewal. Entering his ninth decade on earth, he finds himself admitted to a nursing home and the old South Africa meets the new one.

Zoe is Hans’s new nurse in the nursing home. Having navigated the old South Africa, She has scars from the dark days of the past and since she has found healing in the present, she is best placed to guide Hans into new space while helping him unpeel the layers of secrecy from his past that has limited him from embracing a nation where skin colour is not meant to be a factor of discrimination. They Got To You Too is a story of discovery, acceptance, forgiveness and healing. It highlights the individual journey of an oppressor the oppressor. In alternating chapters, the lives of Hans and Zoe are peeled back and we see how each has arrived at their present station in life. The future is a product of what we make of our past in the present. Only in confronting his past can Hans die with no grudge and baggage.

They Got To You Too is a simple story with deep consequences. It is sensitively told with great empathy. Some may conclude that the story is too simplistic, especially those who still bear the brunt of the evil of the past in South Africa. However, it is a story that gives cause for reflection and provides an avenue for reflection as long as there is a valid reckoning of the past.

3.2/5