Japa, which is the Nigerian slang for migration is a Yoruba word which means “to flee”. Migration has always been a thing among the Nigerian elite and upper middle class. From as far back as a century ago, young and even not-so-young Nigerians have travelled abroad to further their education and often either stayed back to work or returned to resume their careers. However, this current trend has made Japa a buzzword in the Nigerian social media lexicon and a recurring topic on its radio stations is unique. The steep economic decline in the polity followed by a persistent wind of globalization for opportunities and talents has made migration a hot-button topic that has refused to cool over the last decade. Literally every urban dweller in Nigeria, irrespective of social class has several anecdotes centred around the Japa syndrome.

A few of these anecdotes have led me to reminisce on the works of fiction that I have read in recent months and years. The verisimilitude of migration fiction is a global feeling. The world has become a global village and migration is not just a Nigerian thing. Whether in Filipino fiction, Nigerian fiction, Indian fiction, Mexican fiction or Ugandan fiction, people are leaving home as they know it and making a new home far away. People are even beginning to reconsider the meaning of home as a concept. Many Lagos residents of eastern Nigerian origin who were born in Lagos and considered Lagos to be home were forced to reconsider what home meant during the last elections. They were suddenly made to feel less than equal and alien within their own country. A good portion of such Lagosians are leaving in search of new homes abroad due to the oppression that has made them reassess their definition of home.

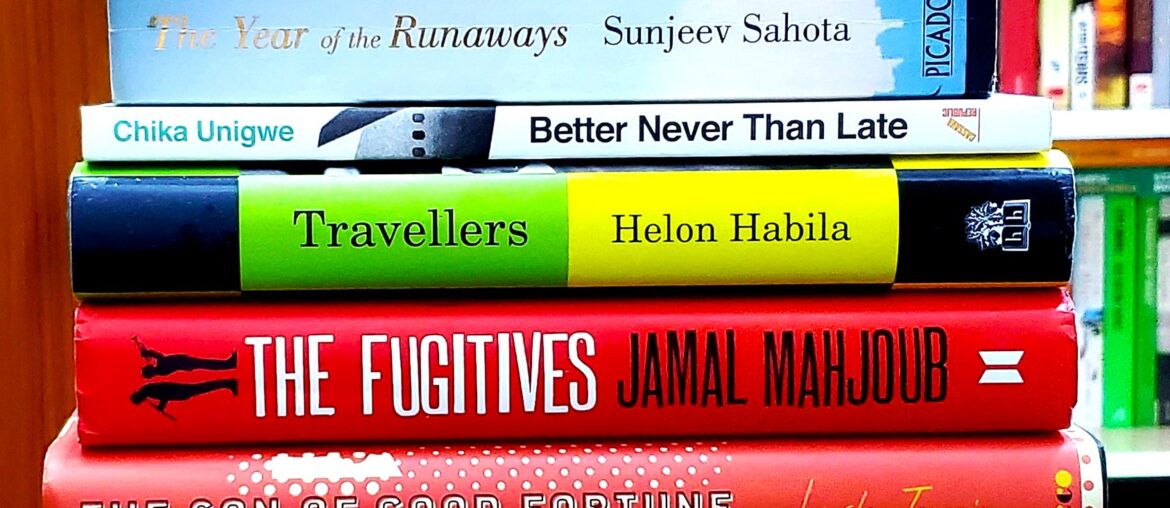

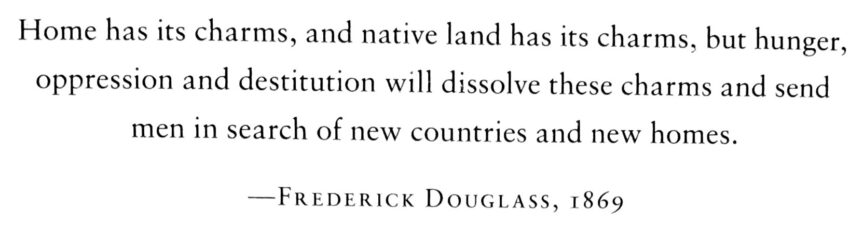

For all the charms of native lands; hunger, oppression and destitution are continually fuelling Japa. Young and not-so-young persons are leaving Nigeria through various routes; you have those who are using the education route – selling assets and possessions and barely surviving abroad in a bid to get a foreign degree that would provide a chance to advance in a new land. This is the route explored in The Year of the Runaways. In it, one of the protagonists goes as far as selling one of his kidneys to be able to fund his migration to the United Kingdom. As economic conditions worsen for the middle class, such fictional tales will be sadly mirrored by reality. The Year of the Runaways is full of people who left destitute homes to meet a set of circumstances different but not distinctly better in a new land. Another sorry state of migration is found in the short stories collection – Better Never Than Late. People like Gwachiwho live duplicitous lives all in a bid to sustain a new life in a new country.

Japa is not restricted to those migrating through the education route or dubious marital relationships as seen in The Year of the Runaway, Better Never Than Late and Dominicana, there are also those who migrate as professionals, as seen in some of the stories in the Short Stories collection, Manchester Happened. This is also the route explored in Travellers. For this set of migrants, despite their professional achievements, a sense of unease remains because rightly or wrongly, they overanalyse every interaction and sense that despite the welcoming smiles, the natives do not see them as equals and even simple questions like “Where are you from originally”is loaded and unsettles them a lot as they rightly expect that their professional attainment and social standing in their new home should make them equals to anyone else. Another set of migrants are first-generation natices. Children of migrants who are born in a new country are continually defined by their parents’ illegal status. This is excellently captured in The Son of Good Fortune. The concept of home is hazy to this set of migrants’ children. They do not feel fully accepted in the country where they are born yet it is the only place they know to call home.

In all of these books, there is one common thread; humans will always gravitate to new lands in a bid to beat hunger, oppression and alienation. The routes for that gravitation differ and the experiences are varied and multifaceted. As Japa intensifies in the face of the relative hunger and oppression in Nigeria, the narratives explored in each and every one of these books will be the lived realities of more Nigerians.