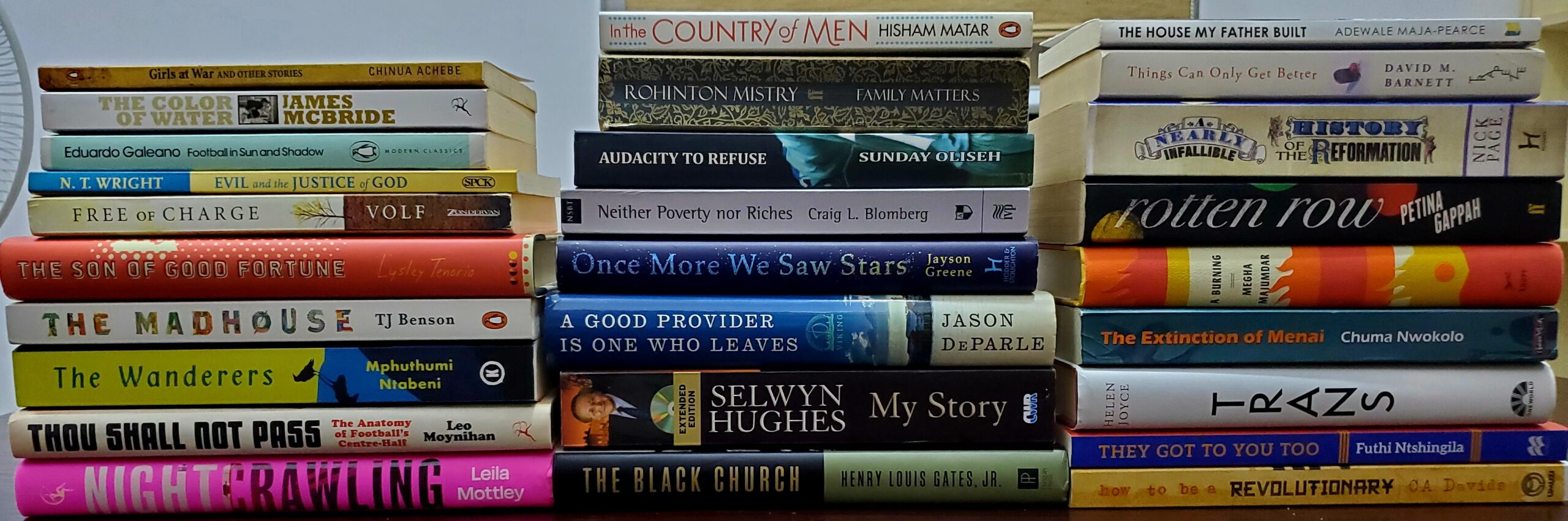

There is one genre of literature that Nigerians are hesitant participants in – Biography (Autobiography). As a people, we are reluctant to tell our personal stories. In other climes, it is common for football stars, artists and even political figures to look back and tell critically acclaimed stories of their careers. I have come to the conclusion that a paucity of such literary works in our society is often due to a lack of introspection, laziness to document and an unwillingness to be challenged. Imagine a society where a presidential candidate has a vague record of his childhood, a questionable record of his source of wealth and even no record of his age. If we had public figures writing decent autobiographies or even allowing access to writers to write their biographies, their stories will be in the public domain and the fact that they can be easily refuted, they will not churn out fantasies. In the face of the paucity of proper biographies, we are left with common tales of “God’s grace and hard work”. Our literary landscape will be richer if personal stories were commonplace. Where authorised biographies compete with unauthorised ones. Luke Chinua Achebe said, “If you don’t like somebody’s story, write your own”.

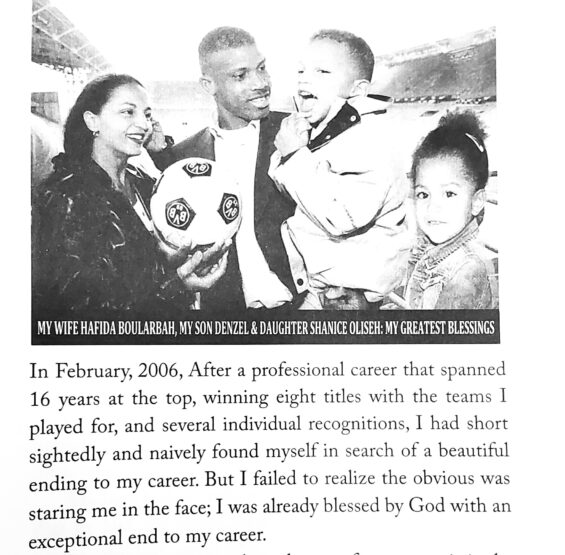

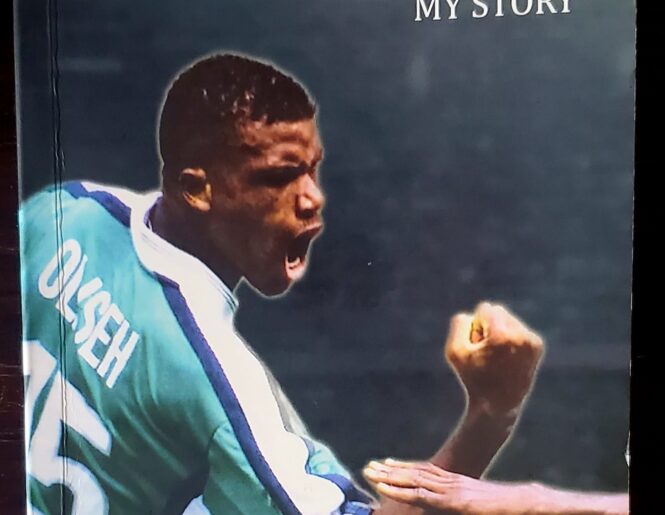

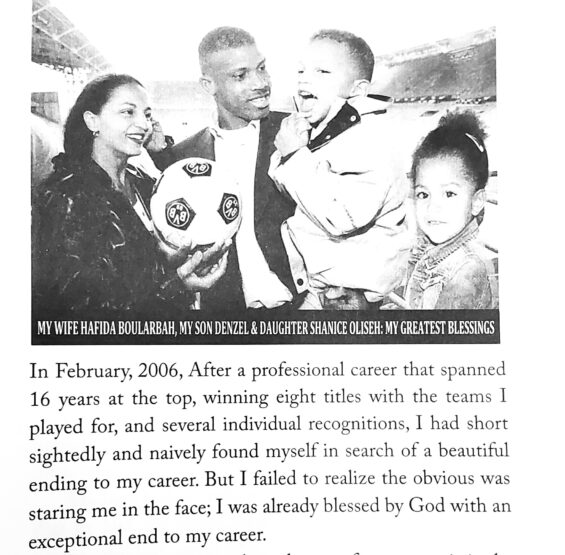

It is for this reason that I found Audacity To Refuse a very refreshing read. Sunday Oliseh’s courageous attempt to tell his story of football success is rare and applaudable. I can’t remember any other football star of his generation finding their success and journey worthy of a biography. Reading Audacity To Refuse refreshed my mind about the time when Nigerian football was glorious. Some of the details that Sunday Oliseh tells in his book are details that I had long forgotten. Some I (as a fan) did not recall as important back then but hearing them contextualized by a primary participant throws a different light on the issues. Sunday Oliseh had a glittering career by all standards. A 16 years career that saw him play in most top European leagues; Belgium, Italy, Germany and Italy. He won league titles in Holland and Germany, was instrumental to Nigeria’s qualification to 3 world cups, and several Nations cup competitions and was captain at several tournaments during his 9 years stint in the Super Eagles.

Audacity To Refuse is Sunday Oliseh’s account of his refusal to give in in the face of adversities – the maladministration that characterized the Nigerian national football teams and the subtle and obvious racism and cultural prejudices that he encountered at his European clubs. The book mostly covers his national team adventures and is less descriptive about his club career. So, it is directed at a Nigerian audience. A lot of research had obviously gone into it as detailed squad lists and lineups are provided to give more context. It is also obvious that this was not ghostwritten as the writing has no literary flavour. The book is not properly structured, the prose is replete with grammatical errors and the football language is extremely pedestrian and devoid of any technical insight. For Sunday Oliseh’s remarkable achievements and pedigree within the context of African football, a collaboration with a proven football writer and an experienced editor was the least that Audacity To Refuse deserved. In the absence of a better-packaged literary product, Audacity to Refuse is a decent testament to Sunday Oliseh’s substantial contribution to Nigerian football and I hope we get to read even better-written biographies from the likes of Mikel Obi, Jay Jay Okocha, Kanu Nwankwo, etc.

2.9/5