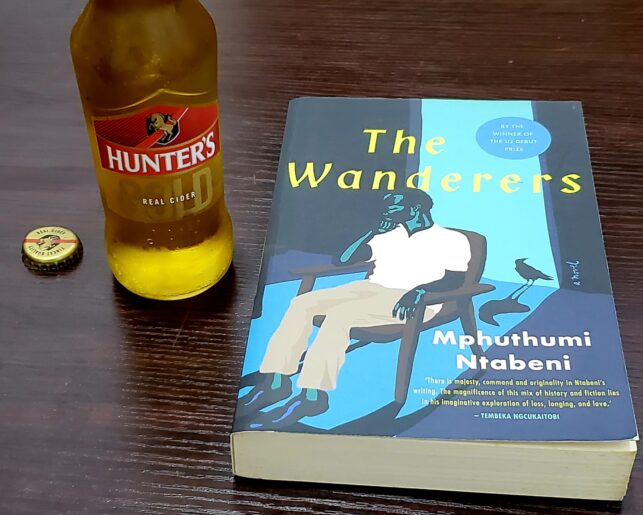

Absence, movement, dislocation and recollection are the overriding themes in Mphuthumi Ntabeni’s The Wanderers. Ruru is 17 years old when her mother, Nosipho died. She became an orphan because her father, Phakamile had died in exile in Tanzania, where he lived since leaving South Africa for political exile in his late teens. During his last days, Phakamile (Phaks) had been collecting his thoughts in a journal and upon his demise the journal was passed to Ruru when she came tracing the path for the father who despite being absent in her life, loomed large. Phak’s journal, an autobiography of sorts, that Ruru uses to piece together her sense of belonging and reconcile her heritage with her present.

The Wanderers is multilayered as it delves into a multitude of themes. Some of these themes are spiritual, some political, some familial and yet some social. At the heart of the social themes of The Wanderers is the family dysfunctionality that is a sad product of the apartheid past of South African society. Families grappling for alignment and reconnection because most males had skipped the border in a bid to avoid arrest, torture and possible death due to their freedom fighting. In the case of Ruru, she had been born and grown into a young teenager in the complete absence of a father. Phaks had been forced to flee town suddenly, abandoning a pregnant Nosipho with not as much as a goodbye wave. Ruru’s restlessness leads her down a path of discovery. This path leads her to her father’s journals. The journal entries were written in Phak’s last days as he was facing imminent death. Musings that spanned theology, classic literature, mythology, and philosophy with an underpinning of the Xhosa culture. These musings are a constant companion of Ruru from the time she is handed the journals during her trip to Tanzania in her twenties. On one hand, The Wanderers is a coming-of-age novel of Ruru, and on the other hand, it is a memoir that encapsulates the thoughts of a wandering soul who is looking back at where his sojourn has led him, what he has lost and gained in the process.

The narrative of The Wanderers alternates between Ruru’s tale in the second person and her father’s memoir in the first person. Ruru’s tale is further split into her sojourn to trace her father’s path and her regular letters to her dead mother who is felt as a guardian angel. The structure of The Wanderers is a major flaw in my view. Alternating from a memoir to a letter to a story from one chapter to the other makes for an uneven reading experience. This is worsened by the uneven timeline. In one chapter, we are reading about Ruru and her Asian roommate in Wits and in the next chapter we are with Ruru and her Tanzanian workmate in Dar es Salam and back to Ruru’s high school days in the 3rd chapter. A more aligned timeline would have improved the reading experience in view of the different genres combine in the book. While I particularly enjoyed Ruru’s coming-of-age story; seeing her go from a seemingly helpless and grief-stricken teenager to one who gets entangled with a sexual predator as a matriculant to a young doctor who learns to negotiate life and love on her own terms. Another arc of narration I found very interesting was Ruru’s visit to Sandi’s uncle. It was a frustrating but reflective narration. Frustrating because it highlighted the sorry state that freedom fighters have plunged their countries into in Southern and Eastern Africa. They have refused to walk the talk. The way the author found creative ways to pastiche classic literature and philosophy into the thoughts and musings of Ruru and Phak is refreshing within the sphere of modern African literature. However, I found Phak’s journal entries tiring and mostly verbose. There was an excessiveness which seemed to overwhelm the arc of the whole narrative. In all, The Wanderers is a reflective read that examines eternal questions. A productive read indeed.

3.3/5