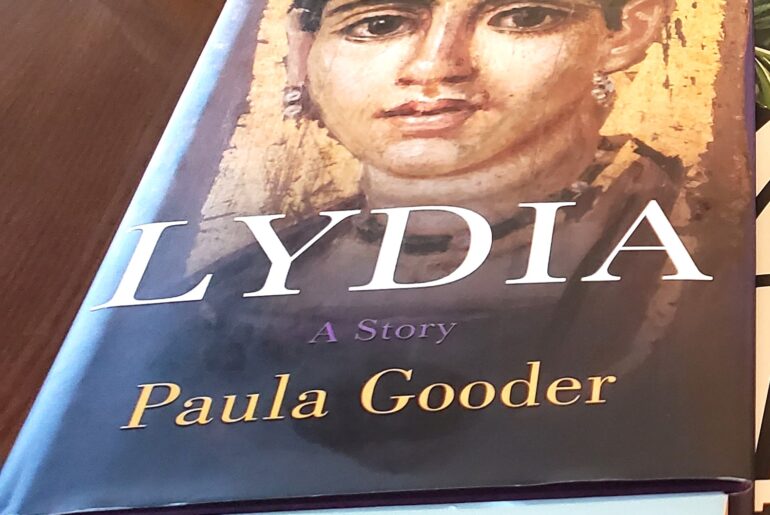

Paula Gooder’s excellent Lydia is a follow-up to the very insightful Phoebe which I read a while back. Both books are very innovative works. It is a genre-defying work; a potpourri of fiction (historical fiction), history, theology and rigorous imagination. In Lydia (Like in Pheobe), the story is an act of historical imagination. The author has allowed her imagination, while guided by rigorous scholarly research, to run wild and create a compelling story around the life of Lydia of Thyatira. Lydia appears very briefly in the bible but there is enough to weave a story around her as a major protagonist and 3 other biblical ladies as minor protagonists – Euodia, Syntyche and the slave girl healed by Paul. The story is set in Philippi and contextualizes Acts 16:16-40 and Paul’s epistle to the Philippians. Conceding the historicity of the New Testament (and particularly the epistles) as a given, there is nothing that brings history to life in the current days like reading a historical text within the context of its original audience. This is what Lydia achieves on a surface level. On a deeper level, it is a theological work empowered by imagination that asks what Paul’s letter to the church in Philippi meant to its intended original audience. The reason why this question is important is that nuance is missing when we look at such historical texts from the lenses of the 21st century but it comes alive more and opens up vistas and layers of understanding that enriches the original text. Through the many characters in Lydia and not restricted to the 4 main protagonists, we get a historically astute view of what the letter meant to various individuals; the slave girl who was healed by Paul, the jailer who got converted after Paul and Silas preached to him, the Jewish members of the Philippi congregation, Lydia (who despite not being mentioned in the epistle is imagined to have been a recipient of the letter since she is from Philippi), Euodia, Epaphroditus and Syntyche who are mentioned in the letter. Through these characters in Lydia, we see that a historical text does not mean the same thing to all recipients. For modern readers, this means that these texts which we consider God-breathed are living and able to speak to us in different times and diverse circumstances.

As much as Lydia is a work of fiction, it is a work of imagination which is bound by a text (Acts 16:16-40 and Philippians) and the interpretation of that text based on the author’s scholarly research. This makes it a story that is not a novel. A work of fiction that leaves the reader with a lot to ponder, introspect and reconsider. It is a refreshing read and I suddenly can’t read the book of Philippians again without imagining what it meant to its original audience and by extension, what it means to me. As much as I loved Phoebe, I love Lydia even more and I can’t wait for the next instalment of this excellent series.

4.2/5